This post is devoted to the study of the mechanisms employed by python ( CPython (3.14) ) to prevent memory-safety violations, including spatial defects such as buffer overflows and temporal errors like use-after and double-free. Additionally, we also cover why python integers can never overflow; this is basically possible due to

This post is devoted to the study of the mechanisms employed by python ( CPython (3.14) ) to prevent memory-safety violations, including spatial defects such as buffer overflows and temporal errors like use-after and double-free. Additionally, we also cover why python integers can never overflow; this is basically possible due to the radix \( \beta\) representation used behind (more precisely radix-\(2^{30}\) system).

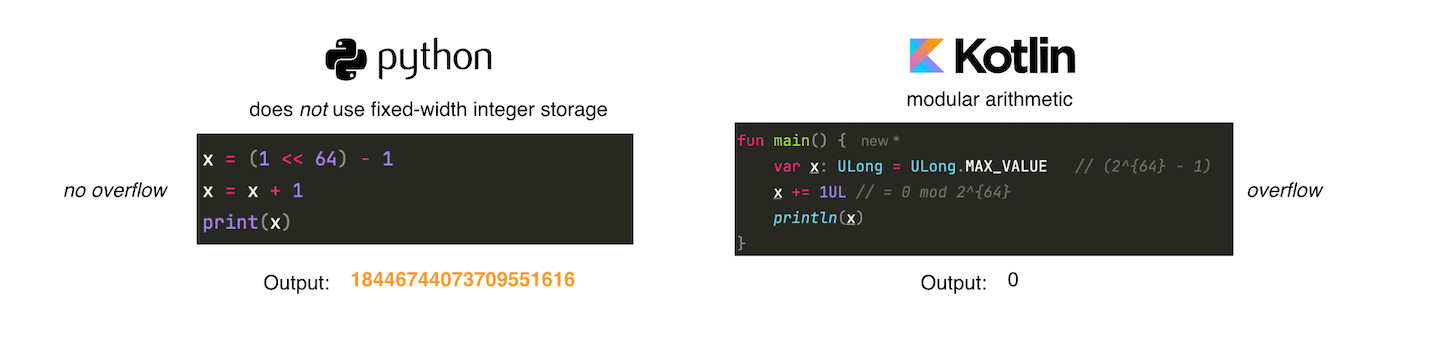

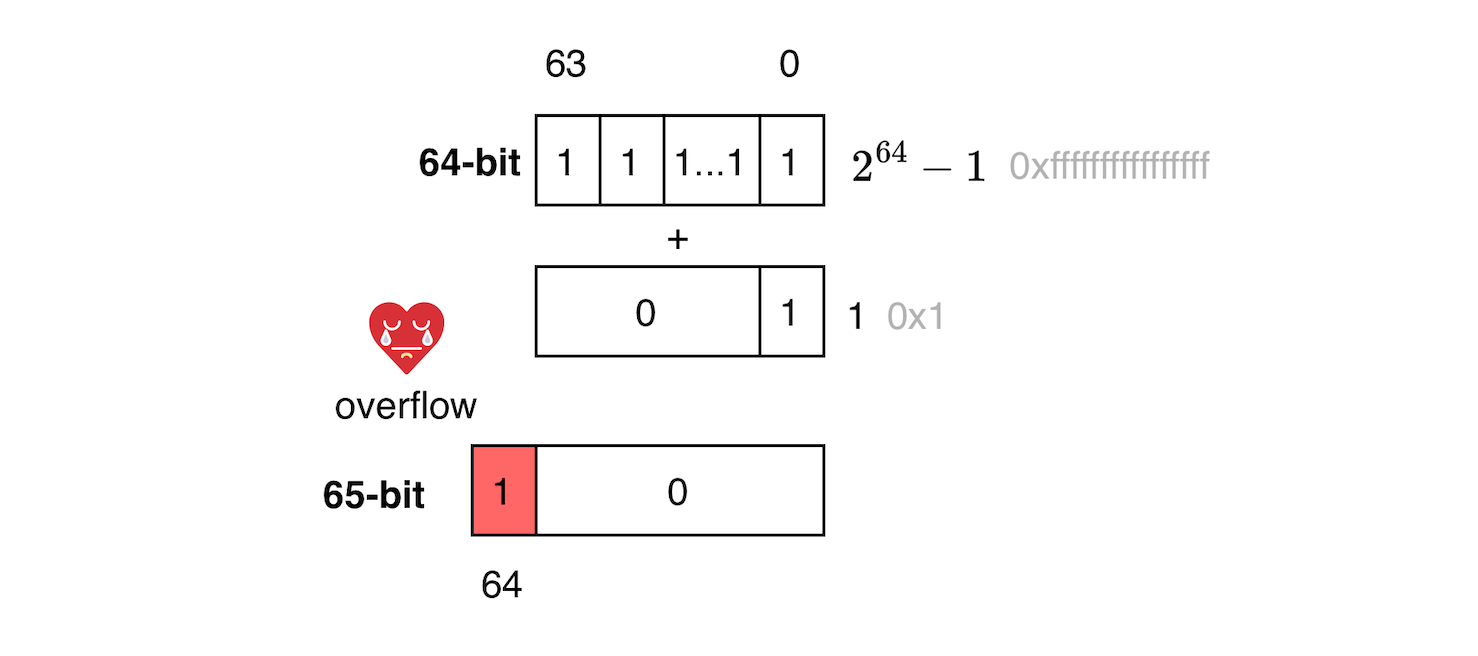

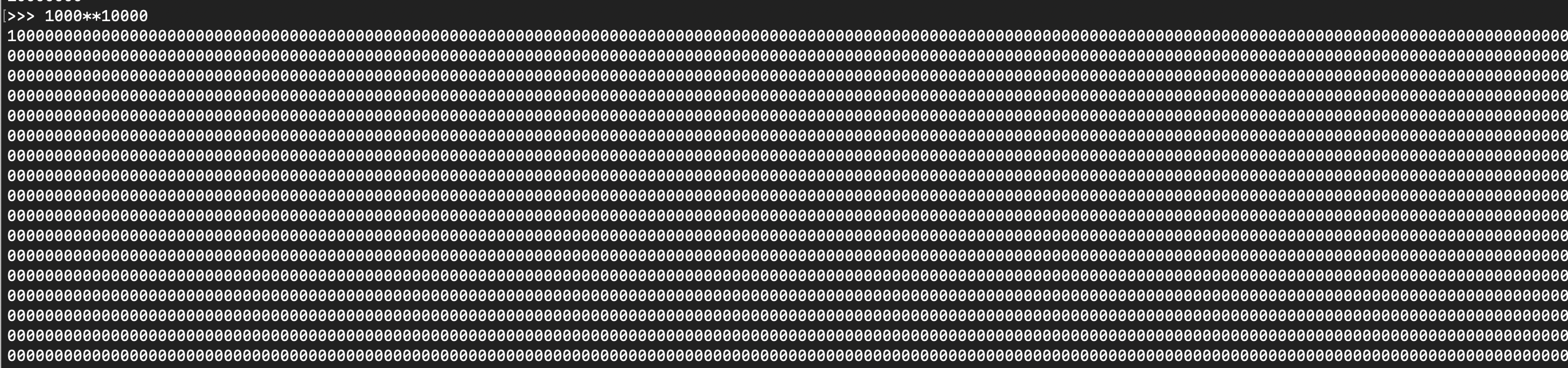

While integer overflow is due to the nature of how computers works (all arithmetic operations are implicitly computed modulo i.e computing and storing happens in a finite ring \(\mathbb{Z_n} = \{0,1,...,n-1\}\)), it can lead to exploitable vulnerabilities. Consider the example below, it attempts to add 1 to 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF (\(2^{64}-1\)) , which results in the value 0x10000000000000000 (does not fit in 64-bit register). When using native JVM primitive, the result is 0, which is 0x10000000000000000 modulo \( 2^{64}\), the bit 65 is discarded due to modular arithmetic. On the other hand, because python has arbitrarily large integers, it does not experience overflow.

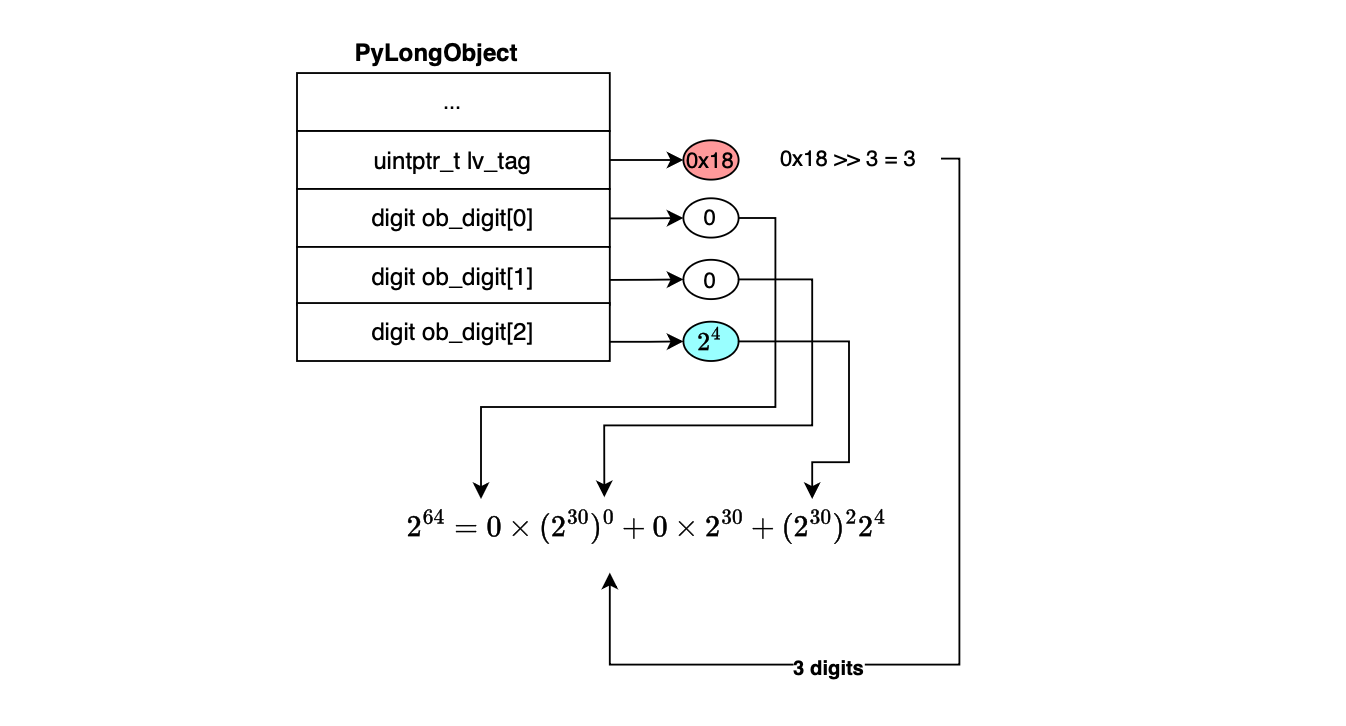

This is how CPython represents \(2^{64}\) in memory.

I have shared my draft notes which can be found at: https://github.com/mouadk/CPython-Through-Cybersecurity-Glasses/tree/main

The section presents a brief overview of how python defeats integer overflow.

The main memory consists of storage or memory cells each with a unique address where the smallest addressable storage unit is one byte, that is, each memory address location refers to a byte, the memory is said to be byte addressable (e.g for 64-bit hardware, the address space is from 0x0 to 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF or \(2^{64} -1 \)). Both data and program data or machine instructions (opcodes and operands that tells the cpu what to do) are hosted in the memory. Each groups of bits that moves in and out of memory is denoted as a word and data is moved from memory to registers (load), from registers to memory (store) and between registers.

Programs, operates on memory by issuing load and stores to specific memory locations. What actually userland programs see are virtual addresses. Every virtual address is translated to a physical address using a page table maintained by the kernel; the translation is achieved by a memory management unit or MMU. In addition to loading and storing, the cpu hardware enables programs to perform bit operations on data such as addition, subtraction or multiplication.

When the cpu needs to access a word from the main memory, it checks whether the data is already present in a cache (cpus are way faster than the ram + cache exploits the principles of temporal and spatial locality). If a cache hit occurs, the requested data (1, 2, 4 or 8 bytes on 64-bit hardware) is extracted from the cache line and placed into a dedicated register (registers consist of a fixed number of bits; access to registers is faster than cache), where it can then be moved elsewhere or used in bit operations by the Arithmetic Logic Unit or ALU. When a cache miss occurs, the requested address is aligned down to the cache line size , and the entire cache line is fetched by the memory subsystem (takes few cycles). Once the cache line is filled, the cpu can continue its work. Naturally, the fewer cache misses a program incurs, the better its performance.

As mentioned earlier, ALU requires data to be placed in registers (in a RISC architecture, all data transfers between memory and the processor must take place through registers). When performing an addition, if the result does not fit inside the destination register’s width (e.g 64 bits), the hardware simply discards the overflow bit and stores the result modulo e.g \( 2^{64}\). In other words, the hardware computes integers modulo some power of 2 and operate using modular arithmetic since values are forced to wrap around within the fixed register width, this is what causes integer overflow!.

Now let us discuss how Python avoids integer overflow using radix-b expansion.

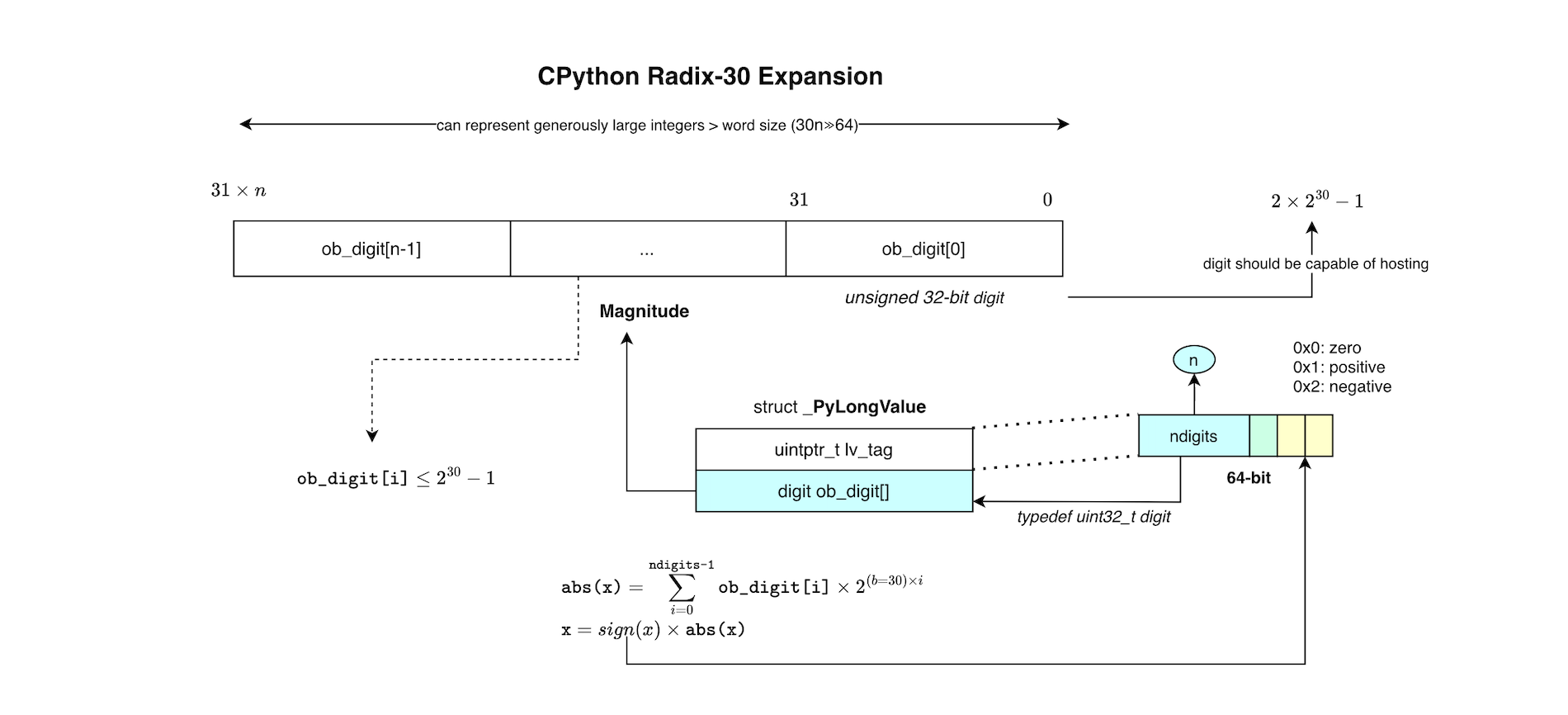

CPython defeats integer overflow by implementing arbitrary-precision arithmetic or big integers. Numbers can be represented in several ways. Most platforms represent numbers in two’s-complement representation (this is where the overflow is experienced due to the register widths limit).

Another way to represent integers is using signed magnitude with base-\(b\) expansion, that is, radix-\(b\) form. The radix-\(b\) representation of an integer \(x\) is a string of natural numbers or digits \(x_i \in \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots, b-1\}\), which could be denoted as \(x = (x_0, \ldots, x_{m-1})_b.\) One can write \(x\) in its polynomial form \(x = s_x \sum_{i=0}^{m-1} x_i b^i, \) where \(s_x\) is the sign of \(x\) (\(\pm 1\)). Any such radix representation is unique.

As depicted below, CPython stores the sign in a dedicated field separately, and the integer vectors are allocated or deallocated on demand, which keeps expanding the polynomial form when needed (each digit uses only 30 of the 32 bits when manipulating the digits; e.g to ensure some intermediate results never exceed a 32-bit integer). This is why it is capable of never overflowing practically.

When adding or multiplying two integers, the virtual machine will make room for more digits if needed and always favor fast paths when possible. To build an integer from a given base, say base 10, CPython uses Horner factorization to construct the limbs. When the source base is binary, building the digit vector is simpler. To print large integers, the Python integer is represented in base \(10^{9}\), and once the digits are created in this new base, printing is trivial (modulo 10, output the character, divide by 10, and so on). If you are interested in more technical and mathematical details, please refer to my shared notes: https://github.com/mouadk/CPython-Through-Cybersecurity-Glasses/tree/main.

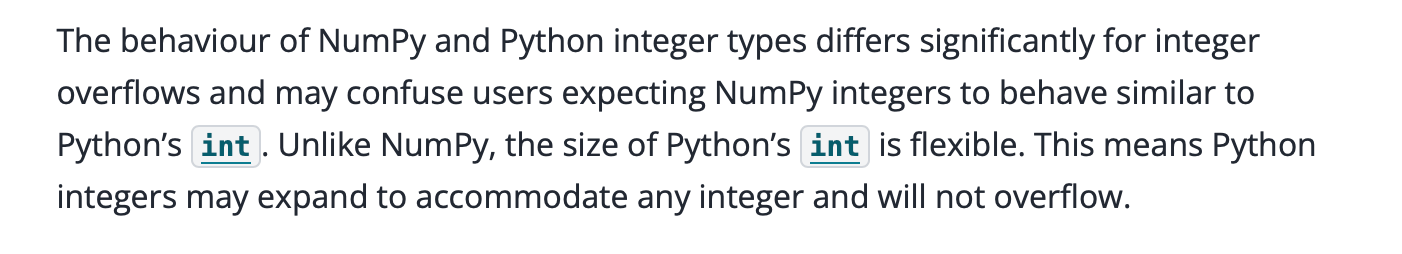

Note, however, that only Python’s built-in integers have arbitrary precision; NumPy integers for instance are not standard Python integers and thus can overflow.

In this section, we look at how cpython prevents spatial memory flaws. In Python, everything is basically a PyObject. We redirect our attention to lists, native arrays and string objects (the idea is really just to show you how virtual machines protects against spatial flaws and also if you want to start hunting for defects :p).

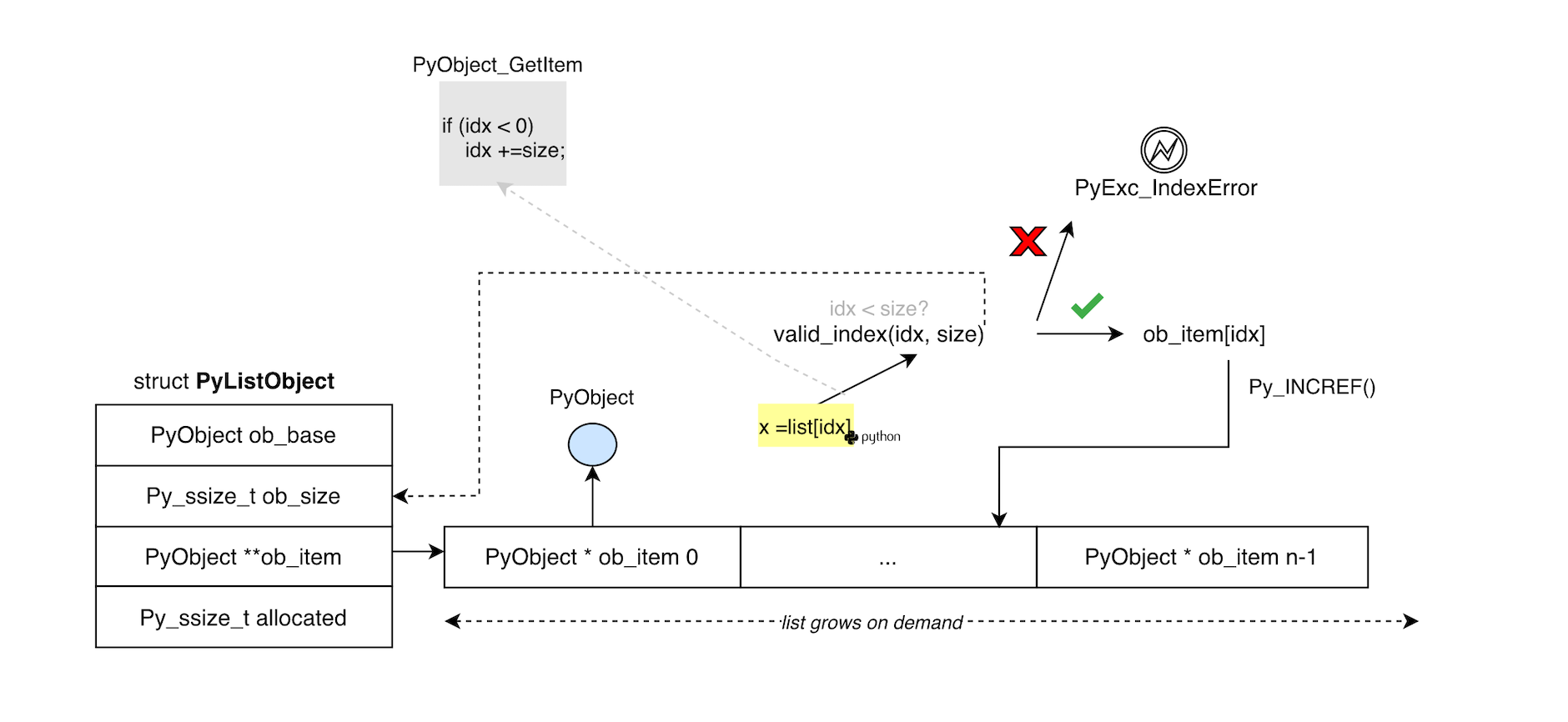

As depicted below, a list in CPython is represented by a PyListObject structure, which contains a pointer ob_item to a contiguous array of pointers to Python objects. When an element is accessed (e.g. x = list[idx]), the interpreter first verifies that the index is within bounds by comparing it against the list size stored in the object ob_size. If the index is valid, the corresponding element pointer ob_item[i] is fetched, its reference count is incremented, and the object is returned.

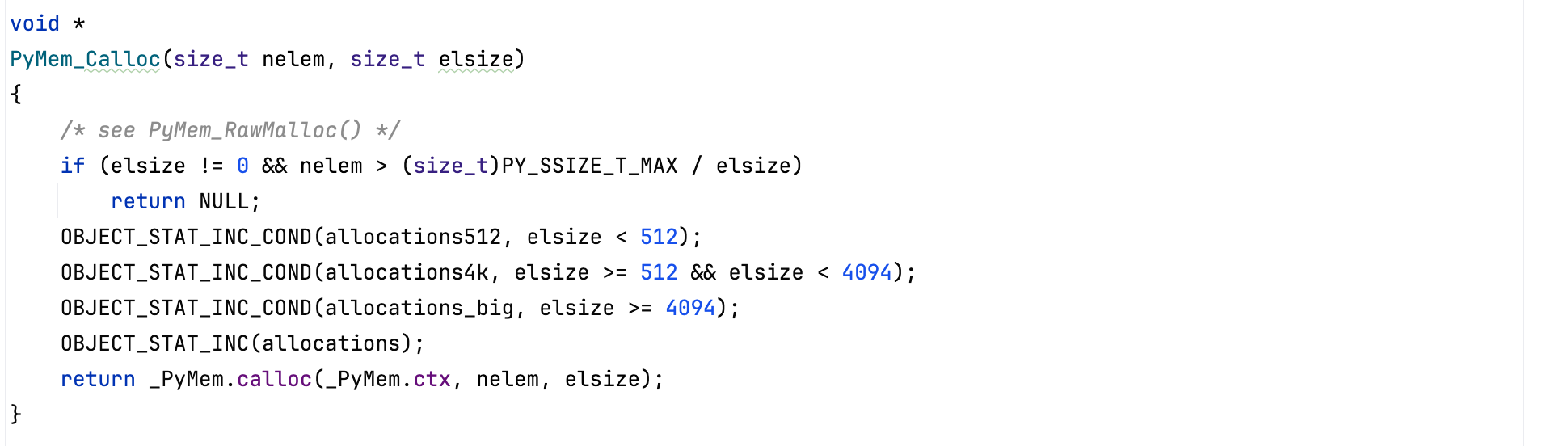

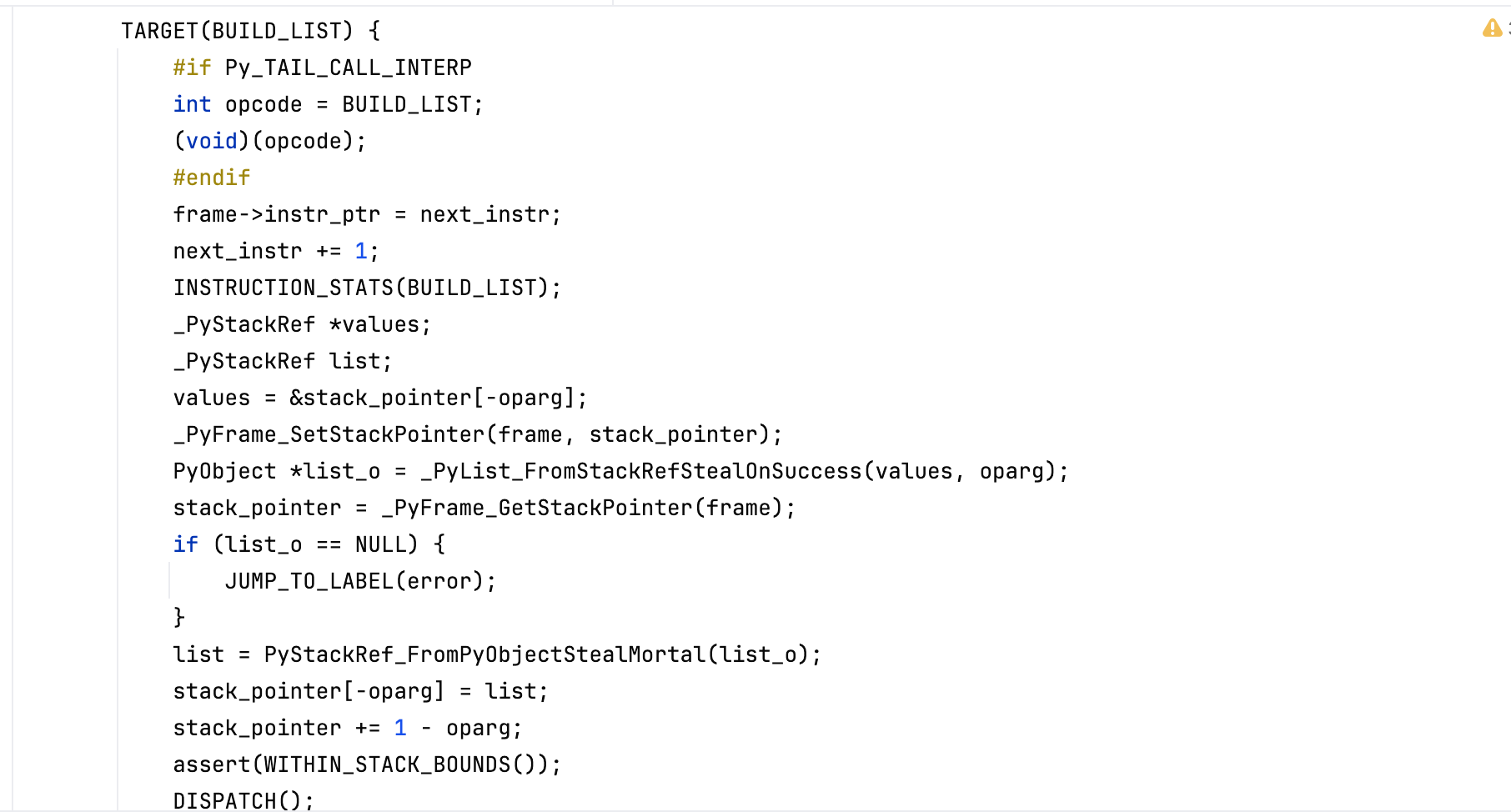

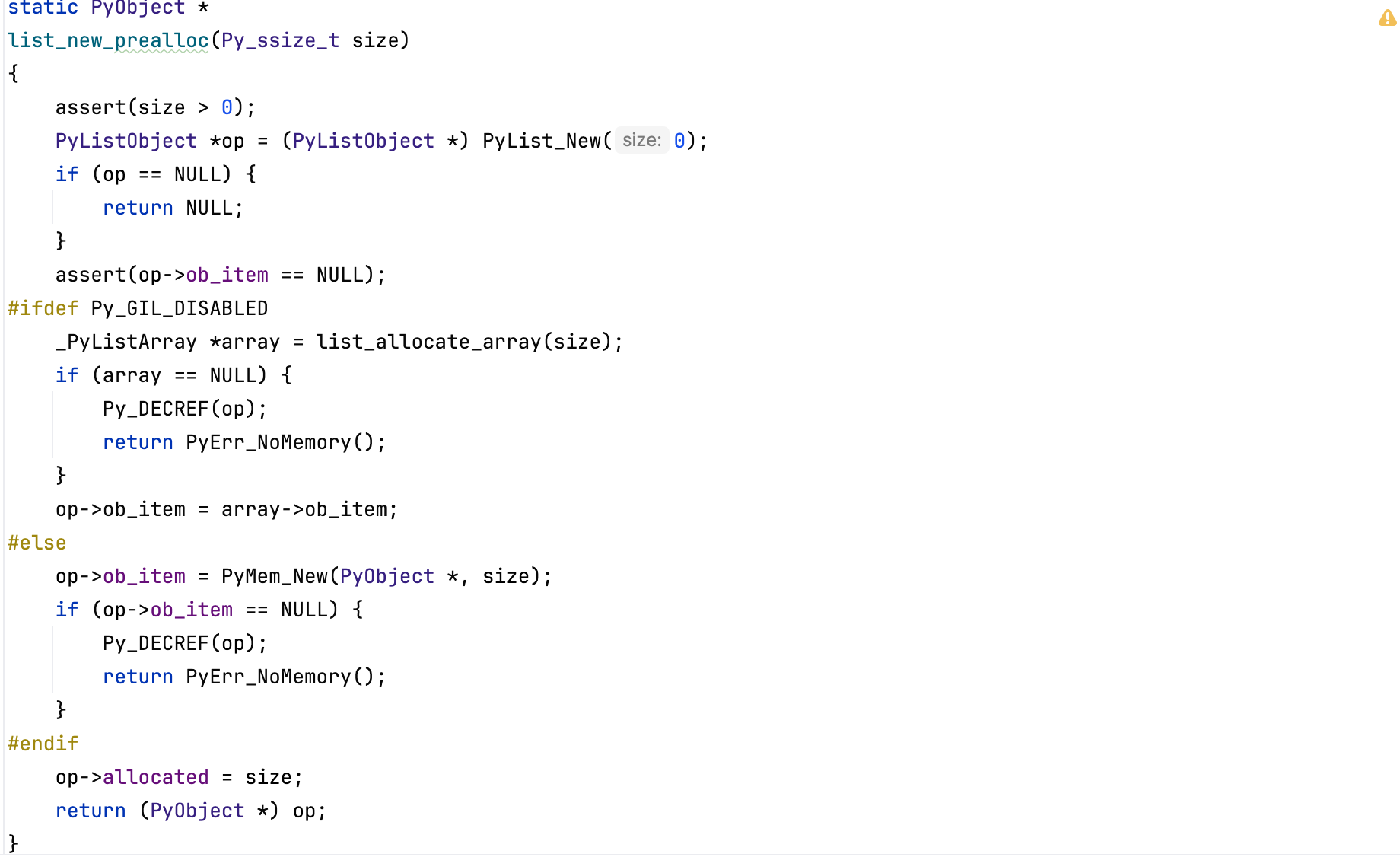

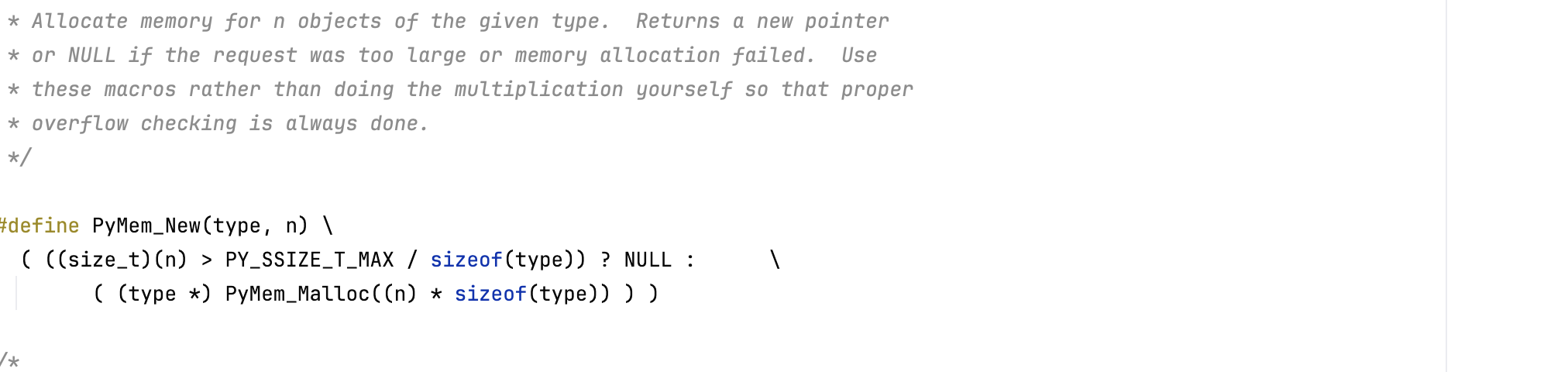

List items are allocated via PyMem_Calloc() (when gil is enabled) which checks for integer overflow (same check happens when gil is disabled):

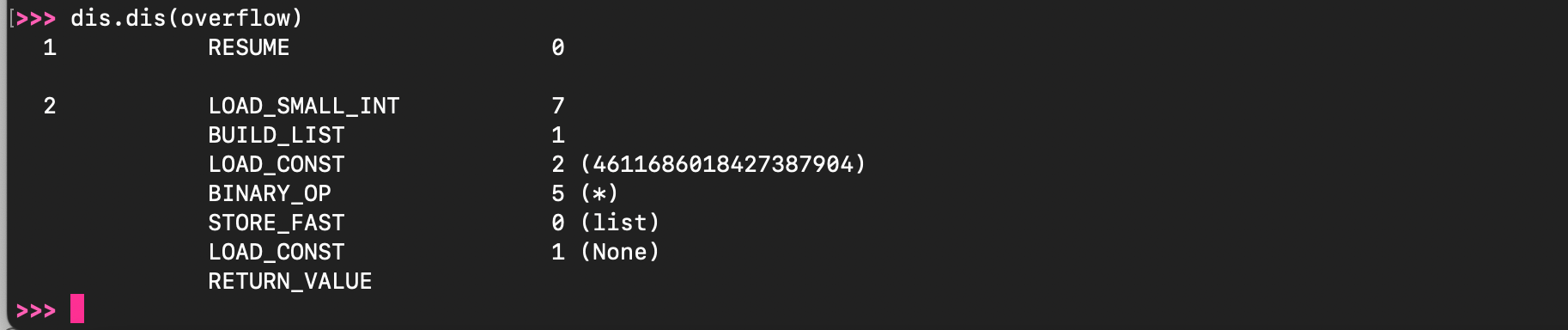

Consider the listing below:

def overflow():

list = [7] * (1 << 62)The produced bytecode looks as follows:

The opcode BUILD_LIST handler creates a list with 1 element (operand) (by invoking PyList_New()) and position the integer 7 in the list.

Next, the binary operation * is evaluated, the interpreter uses sequence repetition to build the final list using list_repeat().

which naturally should overflow during memory allocation.

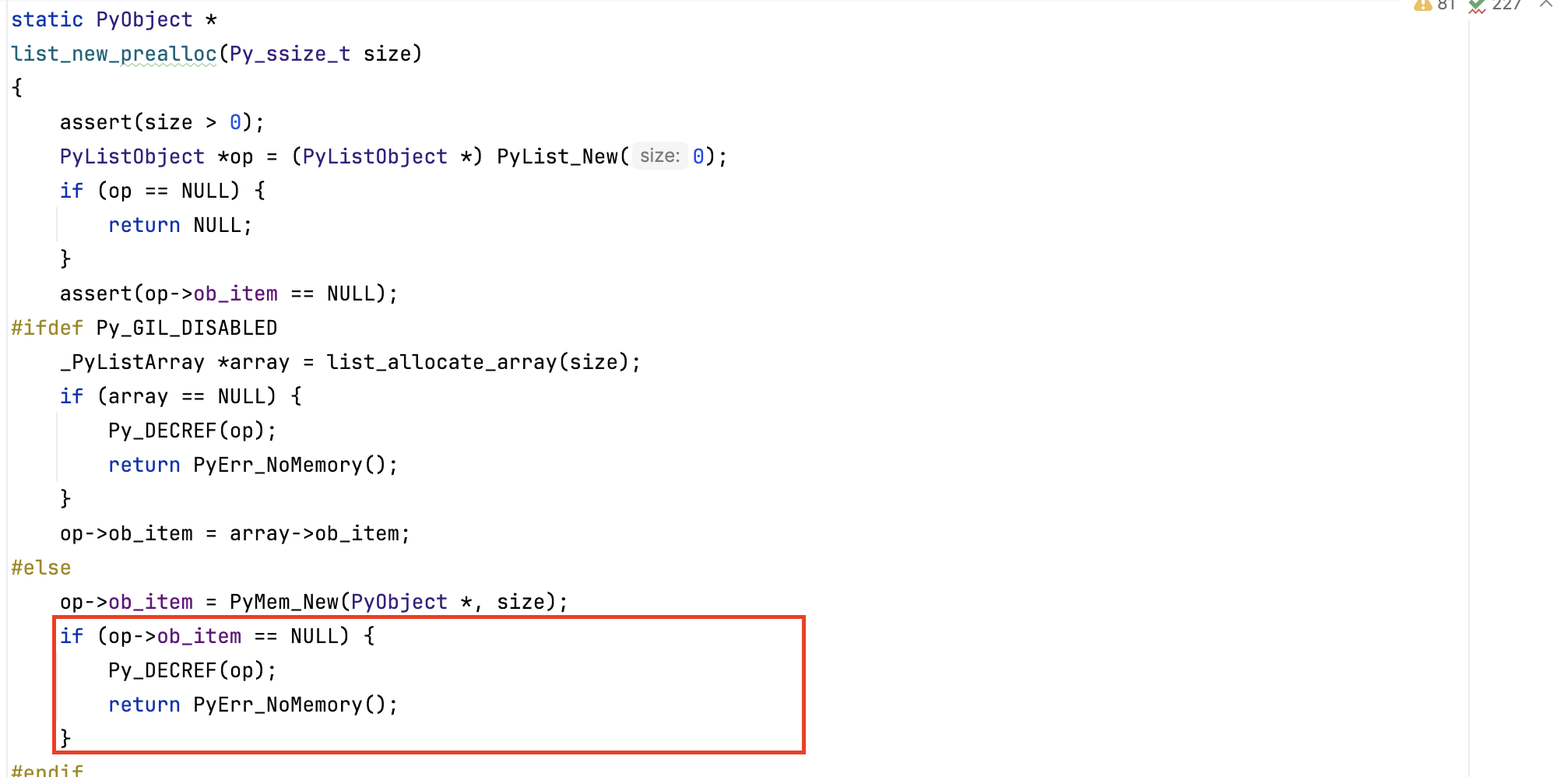

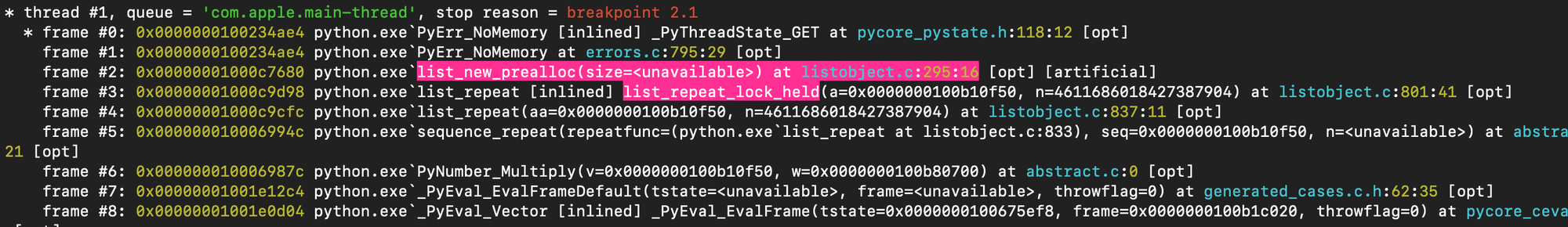

As shown below the interpreter exits by returning a memory error (\(1<<62) \times 8 > 2^{63}-1\)).

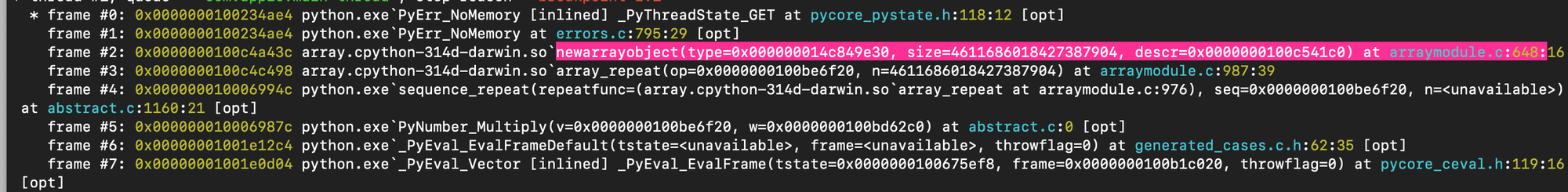

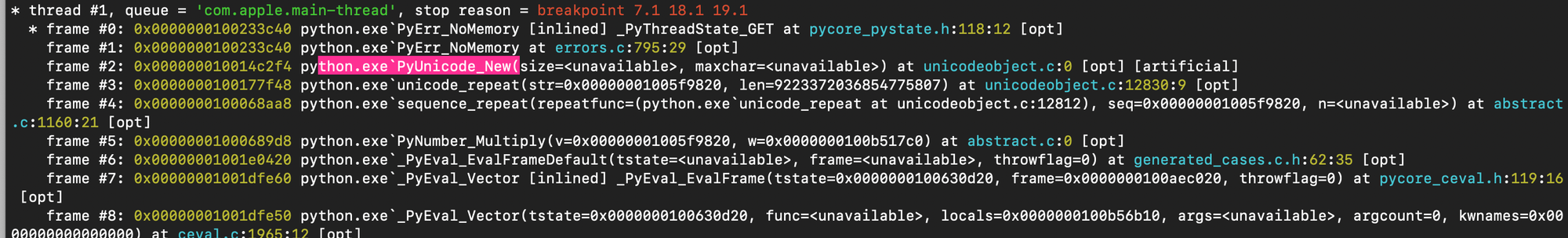

The output of the debugger confirms what we just said:

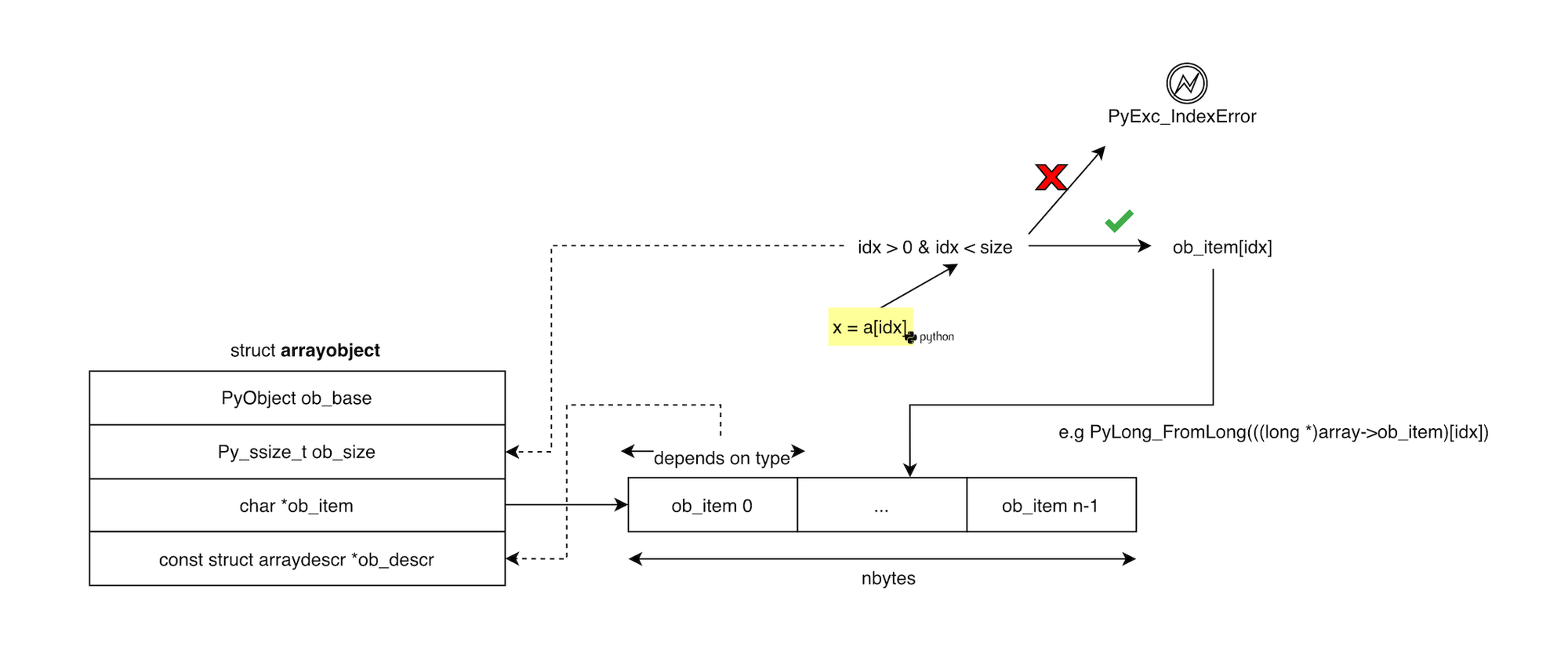

The same principle applies to CPython’s native array.array type, except that it stores raw c data rather than pointers to Python objects. Each time an element is accessed, the interpreter checks that the index is within bounds using the size stored in the array object. If the index is valid, the raw value is read from the underlying memory buffer, converted to an appropriate Python object, and that newly created Python object is returned to the user.

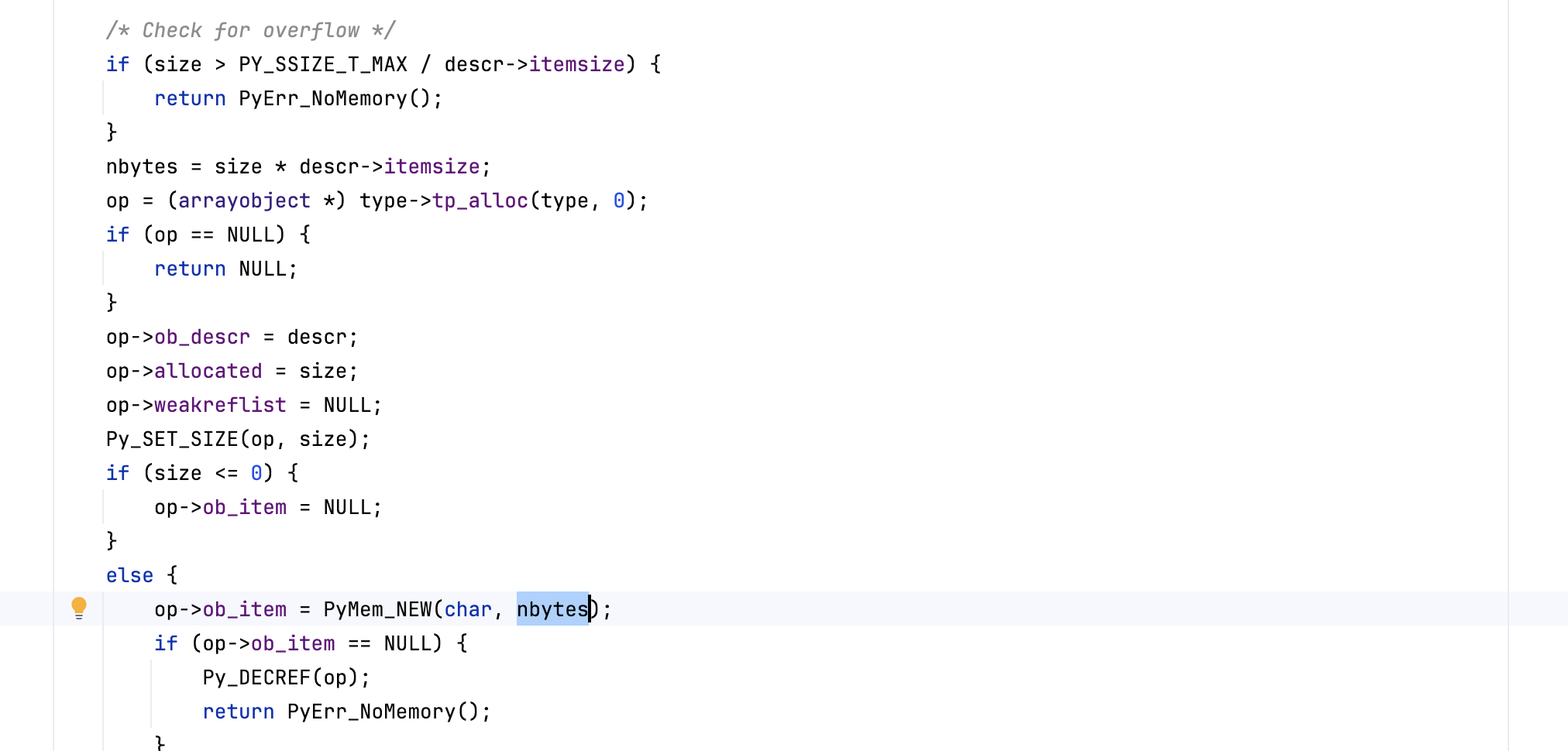

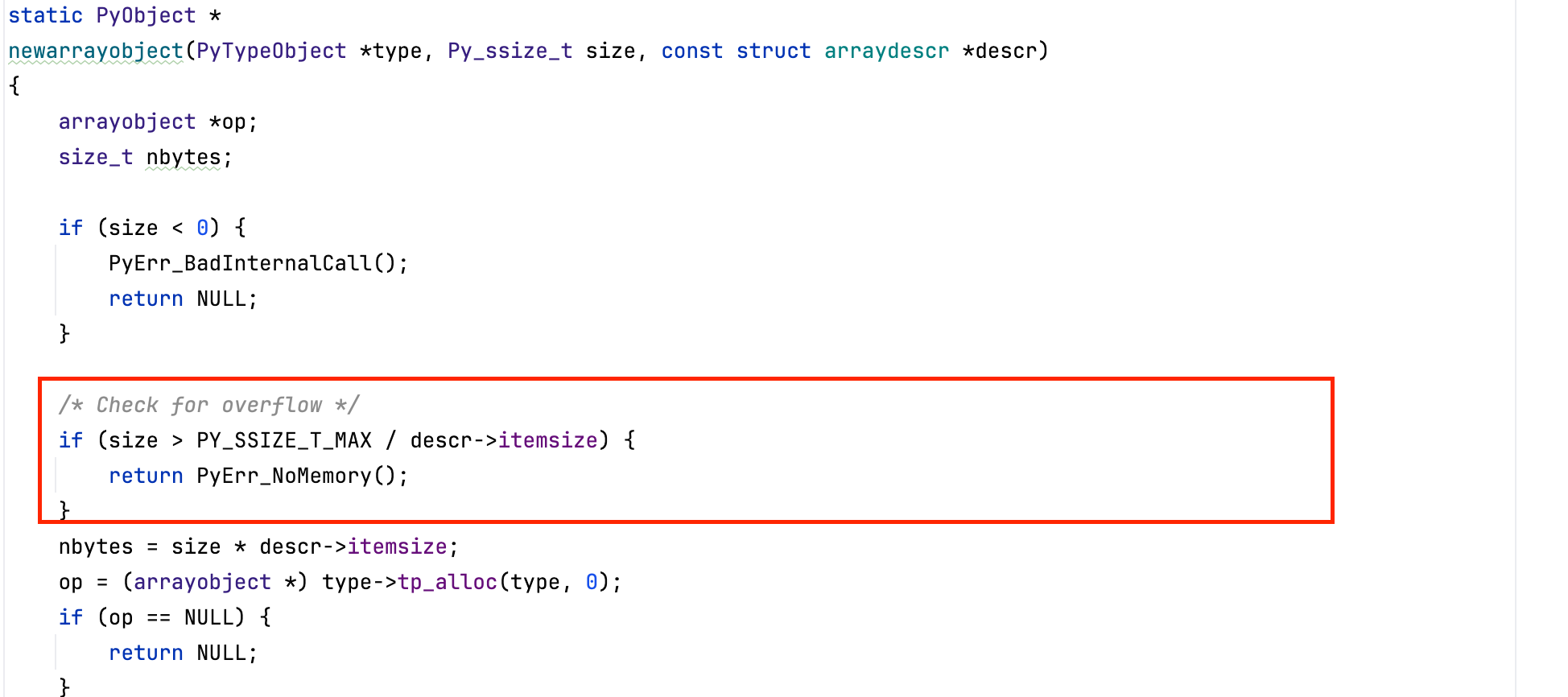

Also, before allocating memory, the virtual machine validates that \( \texttt{size} \times \texttt{itemsize} \) will not overflow (before calling \( \texttt{PyMem\_Malloc()}\) ).

Similar to the previous example, repeating the array 1 << 62 times overflow once multiplied by sizeof(int).

One can use the debugger to verify the path that lead to the memory error.

Each string belongs to a language space described by an alphabet. An alphabet set consists of characters (which make up languages); we humans can comprehend visually what the character is because we learn to do so. However, machines need numbers, so the Unicode idea is to assign to each character a numerical value, a Unicode code point, denoted by U+ followed by a hexadecimal number. For example, U+03C6. Characters are said to be in the range of legal Unicode points U+0000 to U+10FFFF (most are unassigned).

Once characters are labeled with code points, they need to be marshaled as byte sequences. A prevalent scheme is UTF-8, which uses 1 to 4 bytes, depending on the range. The range U+0000 to U+007F contains ASCII characters and they are encoded simply as 0x00 to 0x7F. Non-ASCII characters always have the most significant bit set and use two or more bytes (which allows recognition). When multiple bytes are used, the first byte has one of the patterns 110xxxxx, 1110xxxx, or 11110xxx, where the leading 1-bits before the first 0 indicate how many bytes follow. The continuation bytes always start with 10 and lie in the range 0x80 to 0xBF (modern UTF-8 uses at most 4 bytes to represent a code point).

Mapping a code point to a byte sequence works as follows. First, the code point range is used to infer how many UTF-8 bytes are needed (e.g., U+0711 lies in [0x80, 0x7FF] and thus needs two bytes). The hexadecimal part 0711 corresponds to the binary 0000 0111 0001 0001. For a two-byte UTF-8 sequence, the encoding provides 11 payload bits, 5 in the first byte and 6 in the second. Taking the lowest 11 bits (11100010001), the first 5 (11100) go into the leading byte after 110, producing 11011100, and the remaining 6 (010001) go into the continuation byte after 10, producing 10010001. Thus, the final UTF-8 representation is 11011100 10010001 (or oxdc91).

The decoding is straightforward, the first byte is above the ASCII range, so the UTF-8 mask applies and the 5 payload bits (11100) are extracted; the continuation byte (10010001) yields its 6 payload bits (010001). Concatenating gives 11100010001, which is 0x0711 i.e. U+0711.

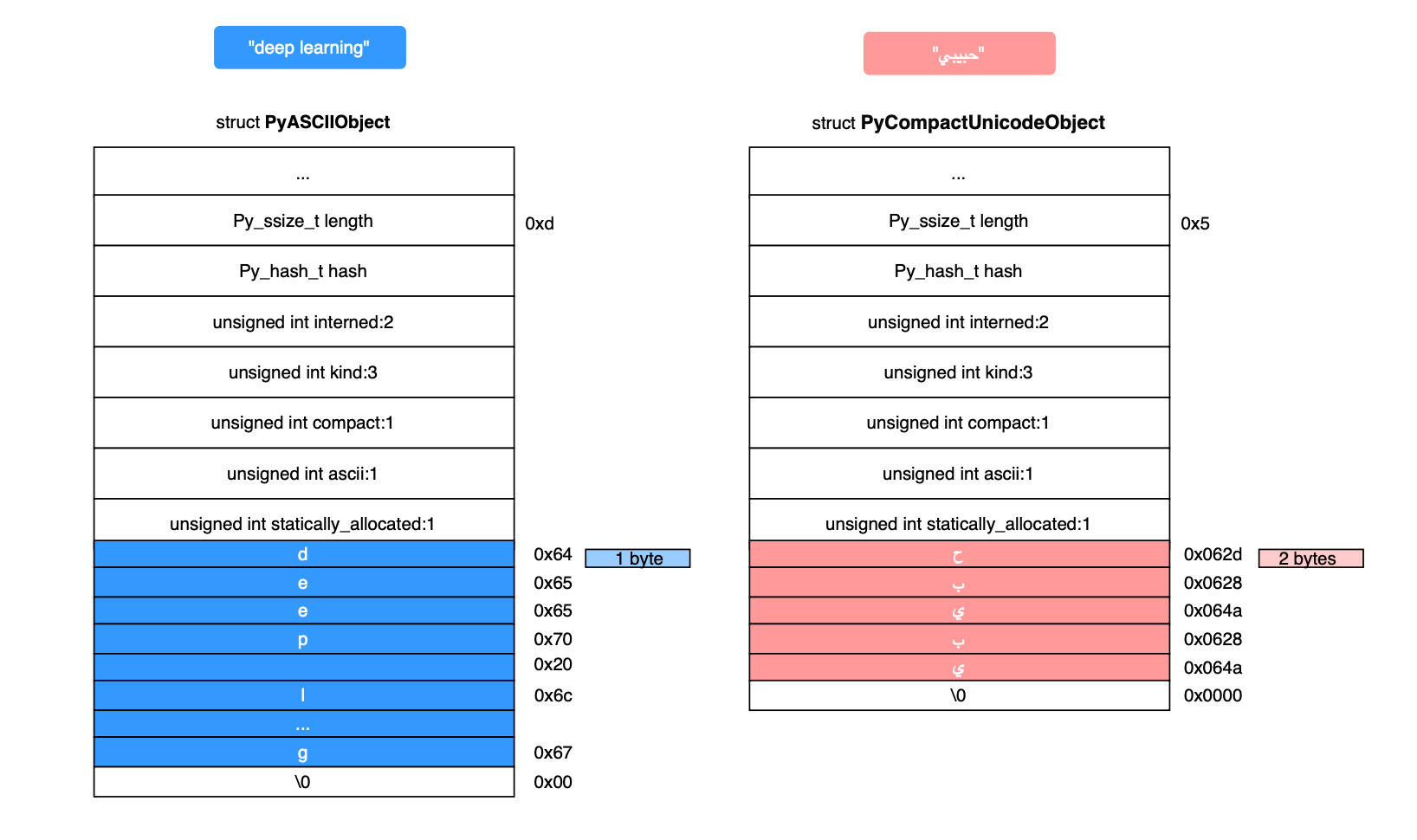

ASCII strings in CPython are represented by the PyASCIIObject structure, while non-ASCII strings are represented by the PyCompactUnicodeObject structure. As mentioned earlier, each Unicode code point requires 1, 2, or 4 bytes, depending on the range in which it falls. CPython supports all three widths and always chooses the most compact representation based on the maximum code point present in the string. If all characters fall in the range U+0000–U+007F, CPython uses an ASCII representation (1 byte per code point). If at least one character is in U+0080–U+00FF, it uses a 1-byte non-ASCII representation (Latin-1). If at least one character is in U+0100–U+FFFF, it uses 2 bytes per code point (see figure below). Finally, if at least one character is in U+10000–U+10FFFF, it uses 4 bytes per code point.

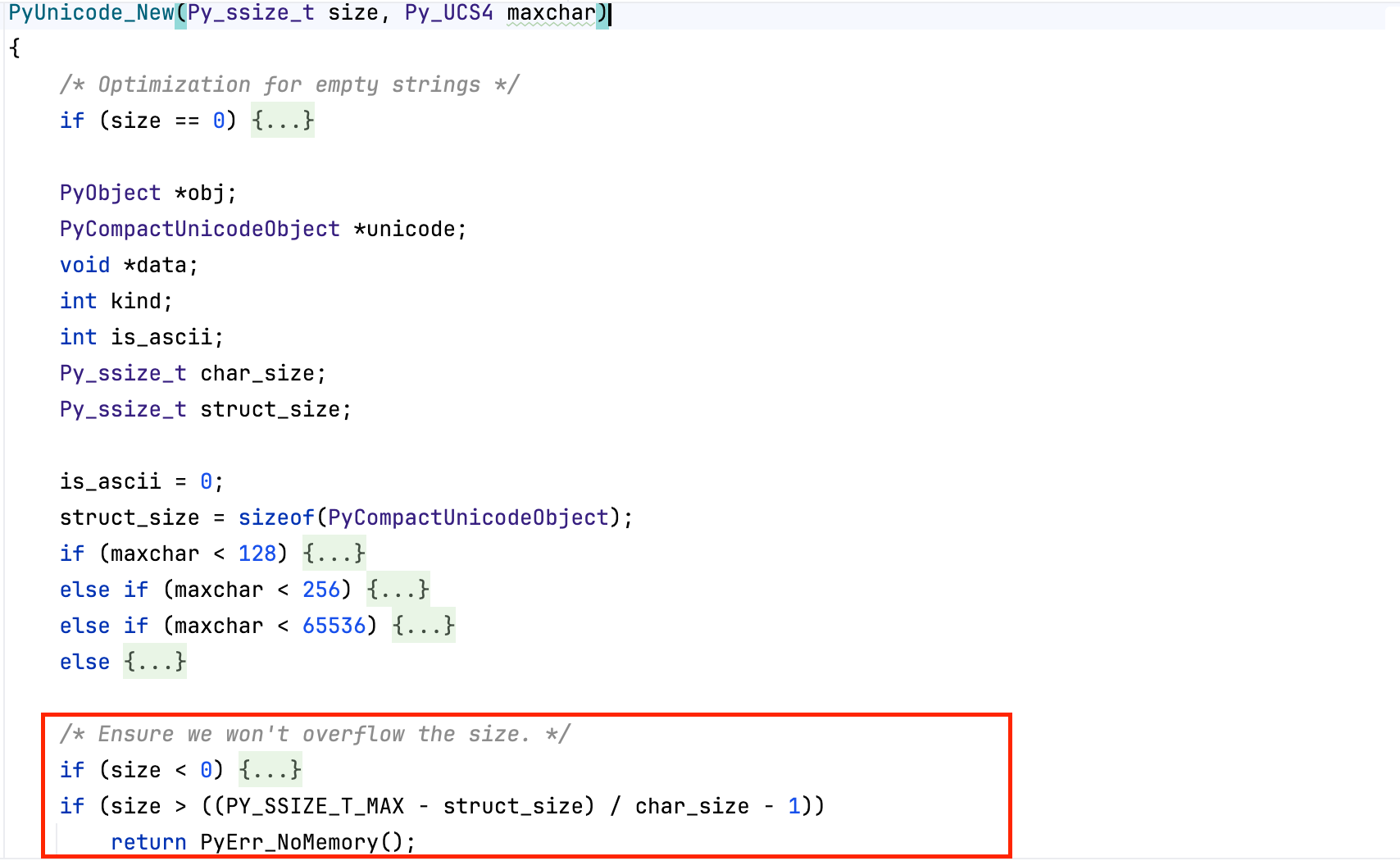

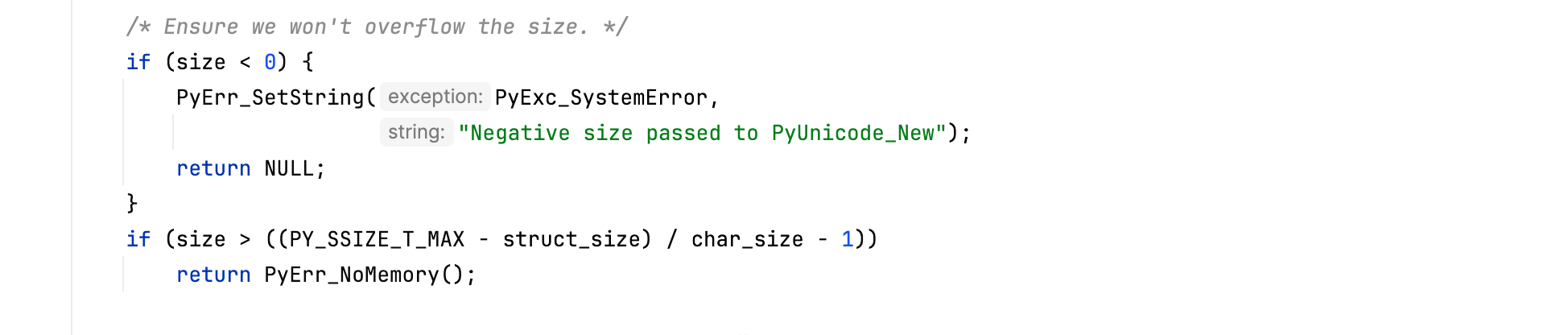

When the virtual machine needs to create a Python string, e.g from a C raw string, it ensures that adding the object’s memory overhead does not cause an integer overflow, specifically, CPython checks that struct_size + (size + 1) * char_size fits within a size_t; otherwise, the arithmetic would wrap around and PyObject_Malloc() would allocate a smaller memory block, leading to memory corruption. The check is listed below.

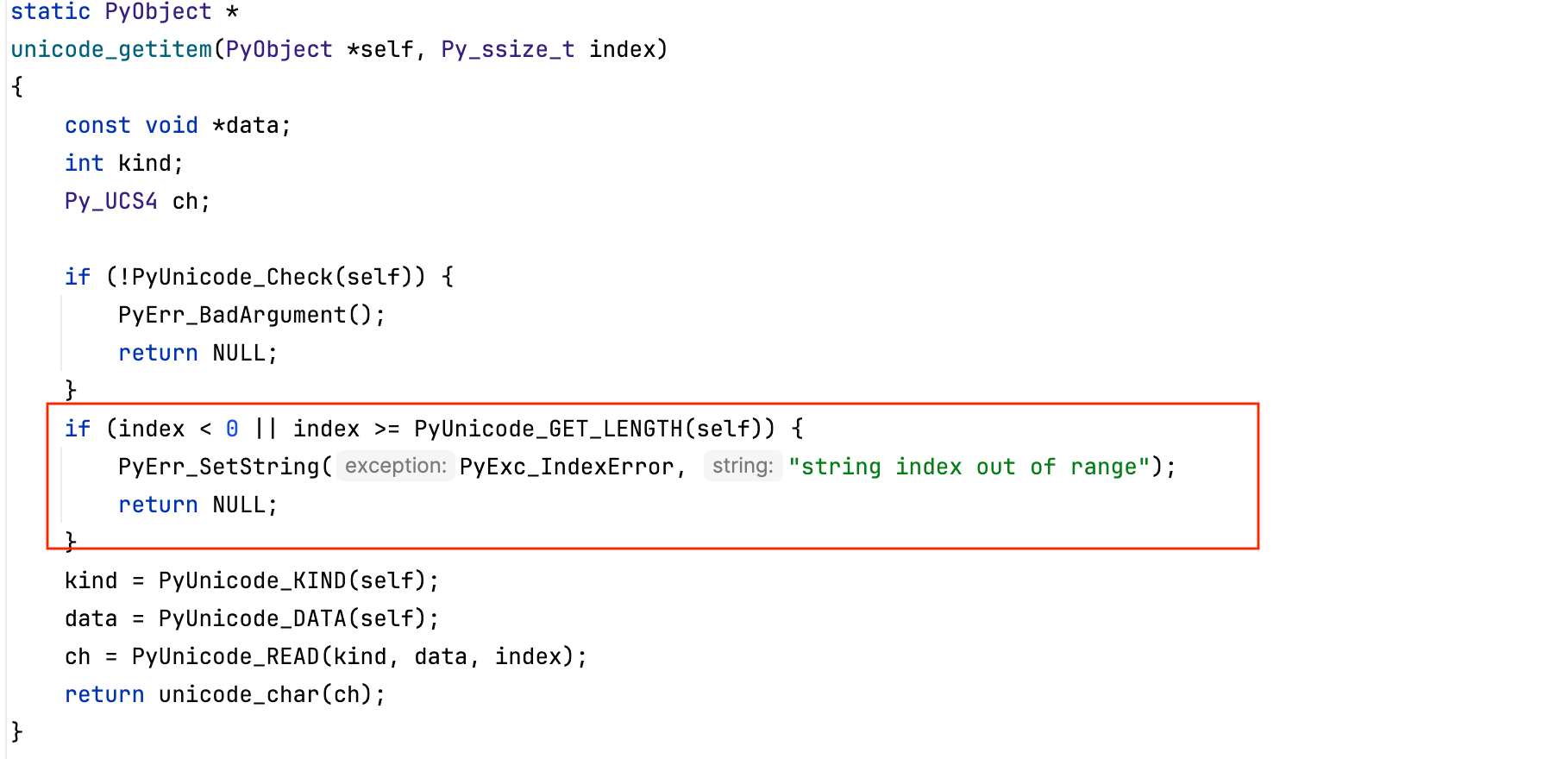

Once a string exists in Python, accessing a character at a given index works similarly to indexing a list, CPython always checks that the index is within bounds, meaning it is not greater than or equal to the length of the Unicode string. Here, length refers to the number of code points in the string, not the number of underlying bytes used to store it.

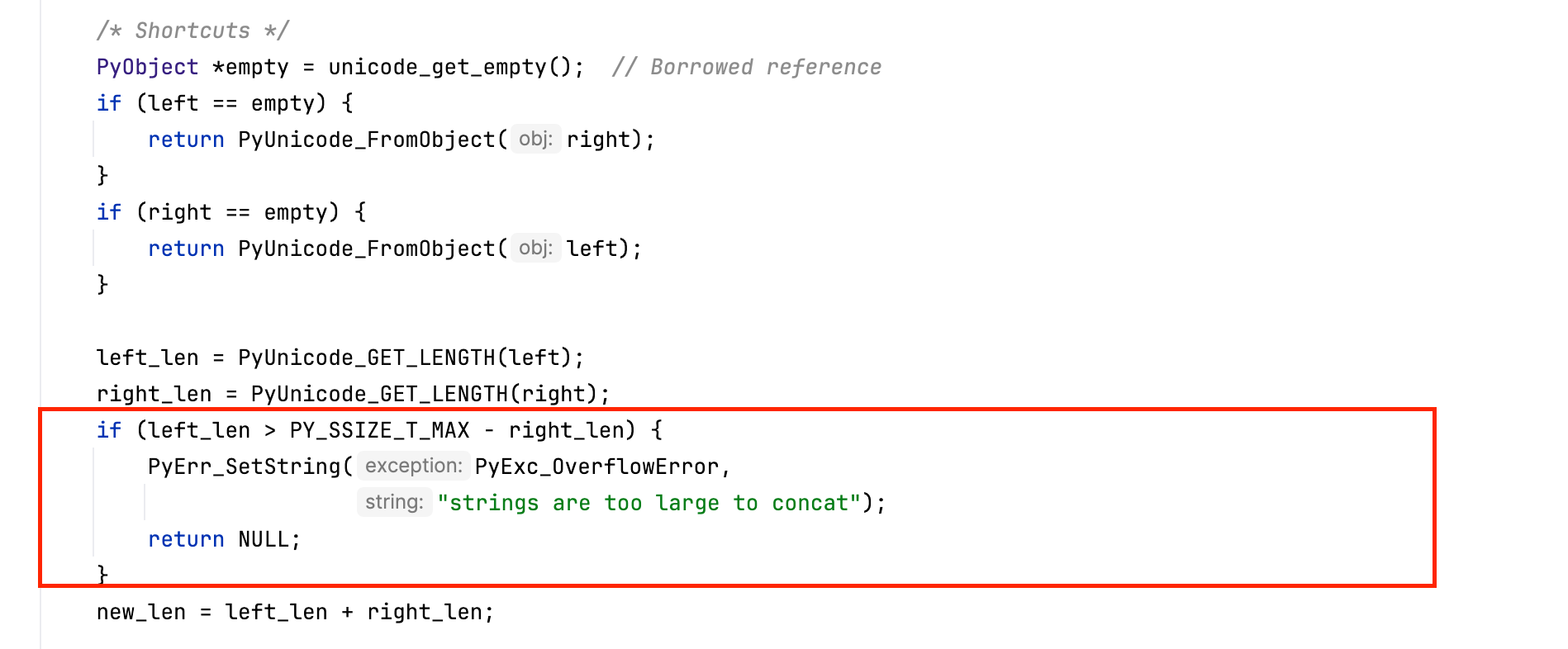

Concatenation or appending is also protected against integer overflow, since memory corruption can occur if the combined string length wraps around. CPython checks that left_len + right_len does not overflow a Py_ssize_t (noting that a naive test like left_len + right_len > PY_SSIZE_T_MAX is unsafe because the addition itself could overflow and bypass the check). Once the length addition is verified to be safe, a new Unicode object is created using the maximum character width of the two inputs to determine the appropriate internal representation, and the character data from both strings is then copied to form the final result.

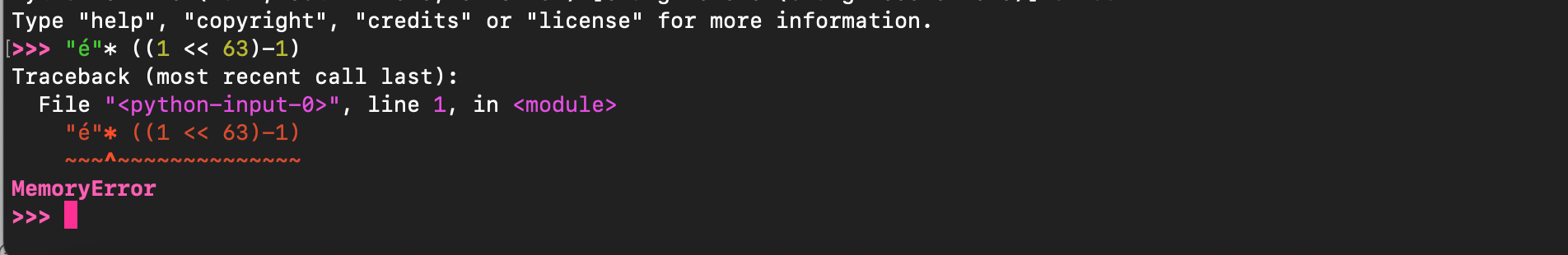

If we take the same example used earlier, the interpreter exits the operation and raises a MemoryError, exactly as expected (as adding even 1 byte to \(1<<63-1\) overflow).

Playing the code and using a debugger, we can confirm what we just said (Py_ssize_t is represented as a signed 64-bit integer).

Instead of allocating less memory than needed the interpreter defeats the violation using the aforementioned check.

This gives a general idea of how memory protection is implemented for string objects.

Programs operate over a virtual address space, where every address manipulated is virtual and mapped to physical memory by the hardware through page tables. The memory provided by the kernel, whether obtained through mmap() or through the traditional heap (brk()), is always page-aligned, since the operating system manages memory in units of pages.

Data structures almost never occupy an entire page, so programs rely on memory

allocators to carve out smaller chunks, maintain locality, reduce fragmentation, and preserve the integrity of internal allocator structures (hopefully). The allocator hands out small regions e.g by invoking malloc(size) and expects the user to return them later with free(ptr).

Dynamically allocated memory is highly subject to temporal and spatial memory errors due to its high usage. When a heap chunk is freed and a pointer is left dangling (referencing freed chunk or object) and dereferenced later, a use-after-free is experienced; this is a temporal error. On the other hand writing past the end of a buffer (due to wrong assumptions or wraps around ) is a spatial defect. Once a buffer overflow or use-after-free occur, dedicated adversaries can steer the memory allocator to achieve arbitrary code execution.

High-level languages such as Python, Lua, or Java take ownership of memory management and attempt to eradicate memory errors and enforce full memory safety. The underlying memory allocator deals with binning, segregated free lists, and page management while the virtual machine handles the automatic memory reclamation using several mechanisms including reference counting and mark-and-sweep scavenging.

CPython actually uses two collectors, reference counting as the primary mechanism, paired with a mark-and-sweep cycle detector to smash cycles.

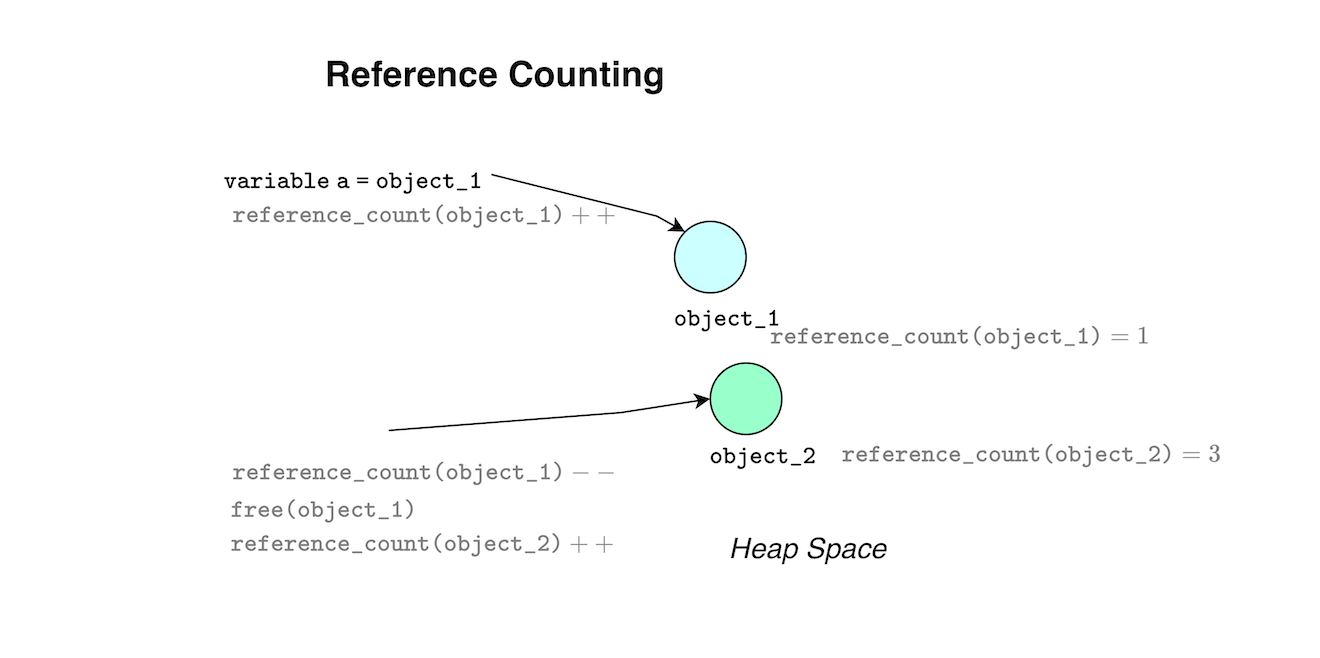

Reference counting is simple to understand, each object hosts a reference count, each time a variable points to the object, the count increases, and when the variable is reassigned or destroyed the count decreases. When the reference count drops to zero the object can be reclaimed.

The problem with reference counting is its completeness due to its conservative approximation. If two container objects reference each other, a cycle is born, and their reference counts never drops to zero (memory leak occurs). Thus Python requires a second scavenger to detect and break cycles (for more details, please refer to my shares notes https://github.com/mouadk/CPython-Through-Cybersecurity-Glasses/tree/main).

From a security perspective, the reference count must be large enough to never overflow (to at least take infinite amount of time); otherwise, a wrap around to zero would incorrectly reclaim an object in a premature way leading to a use-after-free violation and memory corruption (e.g increment by 1 two times to overflow and then decrement). So, if a runtime uses only a few bits for the reference count (eg 1 byte), then it must explicitly handle overflow, otherwise the runtime is unsafe.

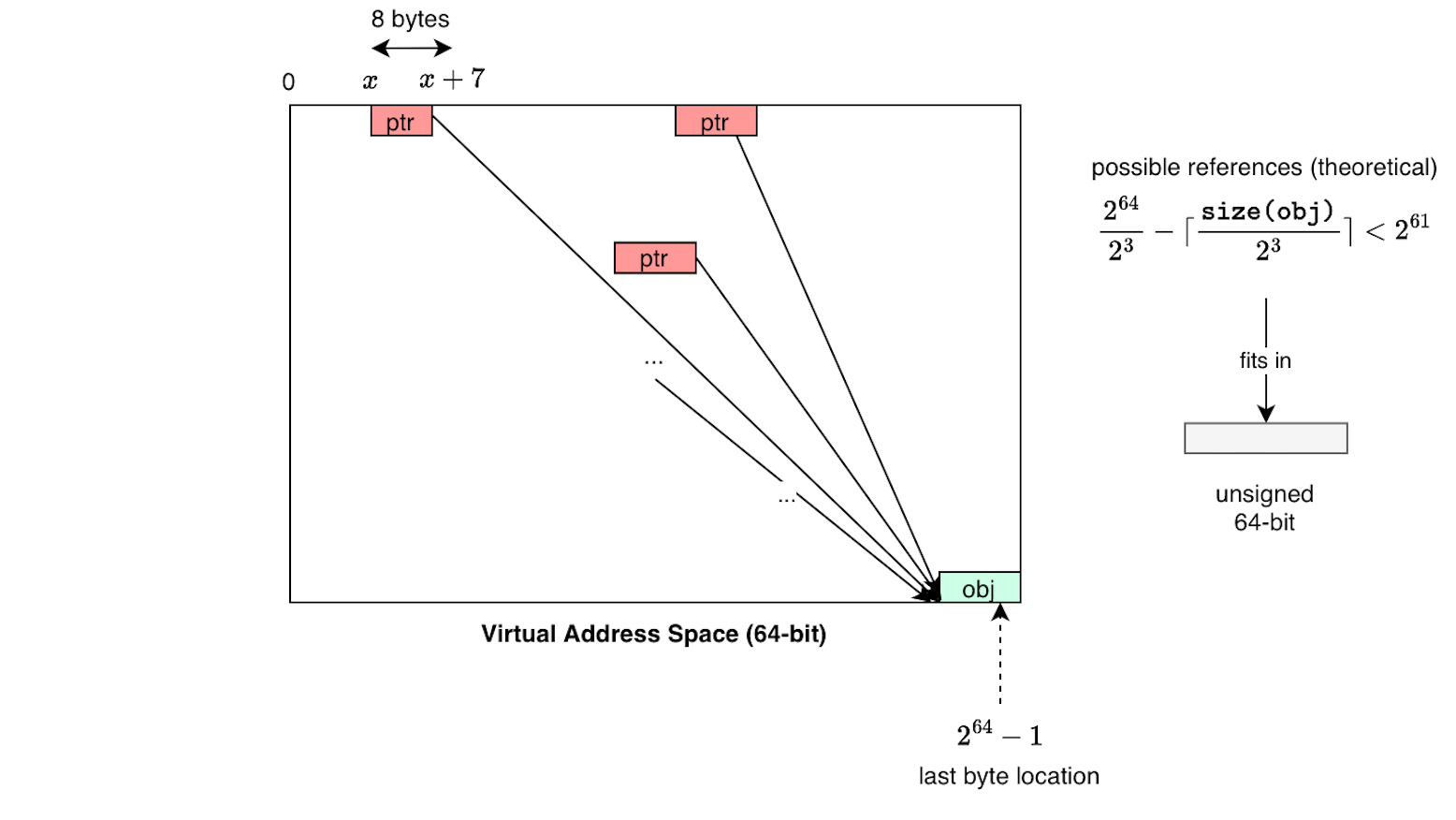

One straightforward way to defeat reference count overflow is simply to store the reference count in a full machine word. For example, in a 64-bit address space, if every single 8-byte word in that address space stored the same pointer, that is, if literally all memory were filled with references to the same object, the total number of references would be \(2^{64-3} = 2^{61}\) which still fits inside an unsigned 64-bit integer. In other words, the reference count cannot overflow as a it can't accumulate more references than the address space can physically store.

For a 32-bit unsigned integer, the maximum value is \((2^{32} - 1)\). To overflow a 32-bit reference counter, one would need roughly 4 billion distinct references \((2^{30})\) to the same object. Each reference must be stored somewhere, requiring at least a pointer’s worth of space. Assuming \(n\) bytes of overhead per stored reference (pointer + metadata), this means that overflowing a 32-bit refcount would require approximately \((4 \times n)\) gigabytes of memory all pointing to the same object. Thus, overflowing a 32-bit refcount is already impossible on 32-bit hardware due to the 4 GB virtual address space limit. Even on modern 64-bit hardware, overflowing a 32-bit reference counter is still not practically achievable, it would require gigabytes of pointer storage, this is paranoia.

For a 64-bit unsigned integer, the maximum value is \((2^{64} - 1)\). To overflow a 64-bit reference counter on a 64-bit system, one would need \((2^{64} - 1) / 2^{3}\) references all pointing to the same object; still fit within a 64-bit integer.

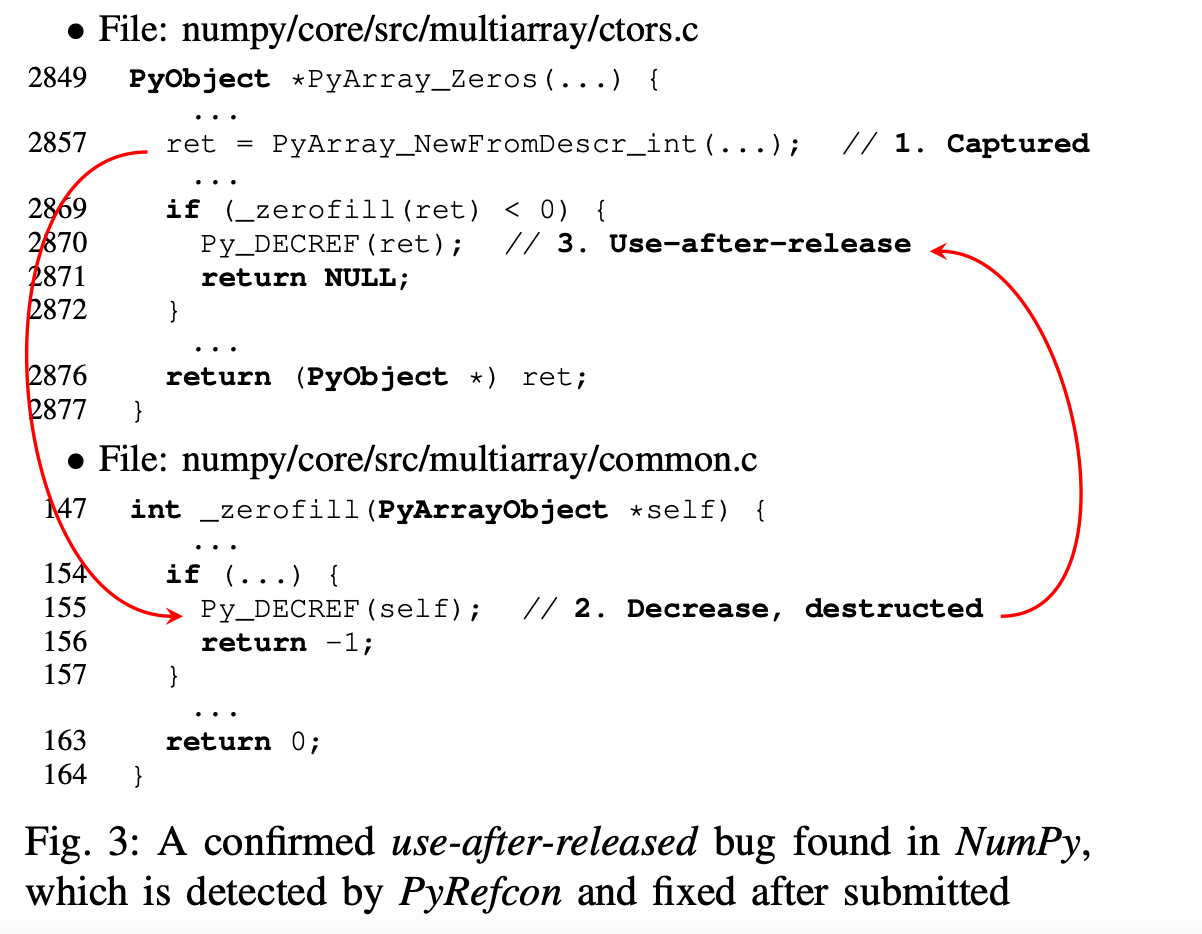

While using a single word-sized reference count is enough to defeat refcount overflow, if the refcount is not manipulated correctly, it can still lead to use-after-free violations (reclaiming the object in a premature way due to decrement then continue to use) and memory leaks (e.g forgetting to decrement the refcount thereby halting its reclamation).

The macro PyObject_HEAD defines the initial header of the object PyObject and houses the reference count used by the reference-counting algorithm for scavenging. When the GIL is enabled, the reference count is represented using an unsigned 32-bit integer, when the GIL is disabled, biased reference counting is employed, one local reference counter uses an unsigned 32-bit integer, while the shared reference count uses a signed 64-bit integer (on 64-bit platforms) or Py_ssize_t. In other words, \(2^{31}\) references to an object are supported (before approaching a refcount that high, a crash would have already been experienced).

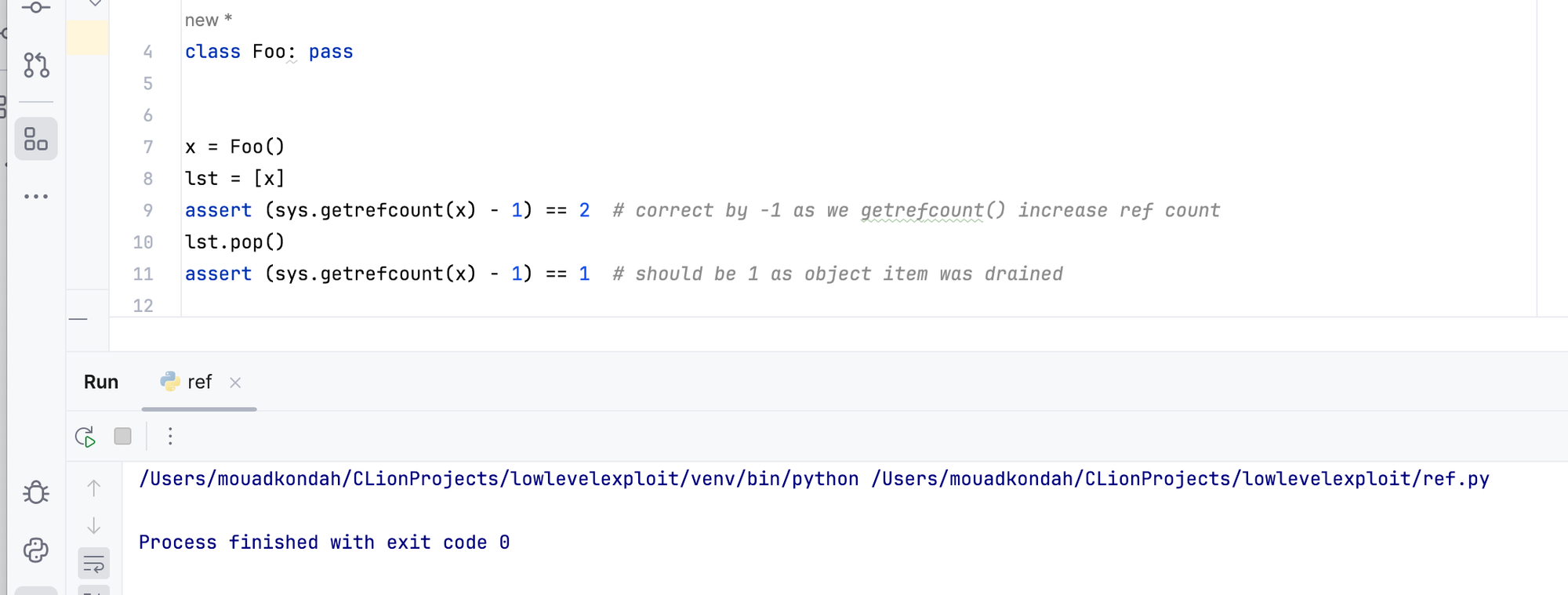

Consider the listing below. A Foo object is created and is referenced by the variable x (increasing ref count to 1), appending it to a list increase the reference count by 1, so one can assert that the expected ref count is in fact 2. Once the element is popped from the list, the ref count should have dropped to 1.

In python land, there is no sys.increaserefcount(), so anything that manipulates refcounts directly happens only inside C code e.g via C extensions (this is where miscounting can occur).

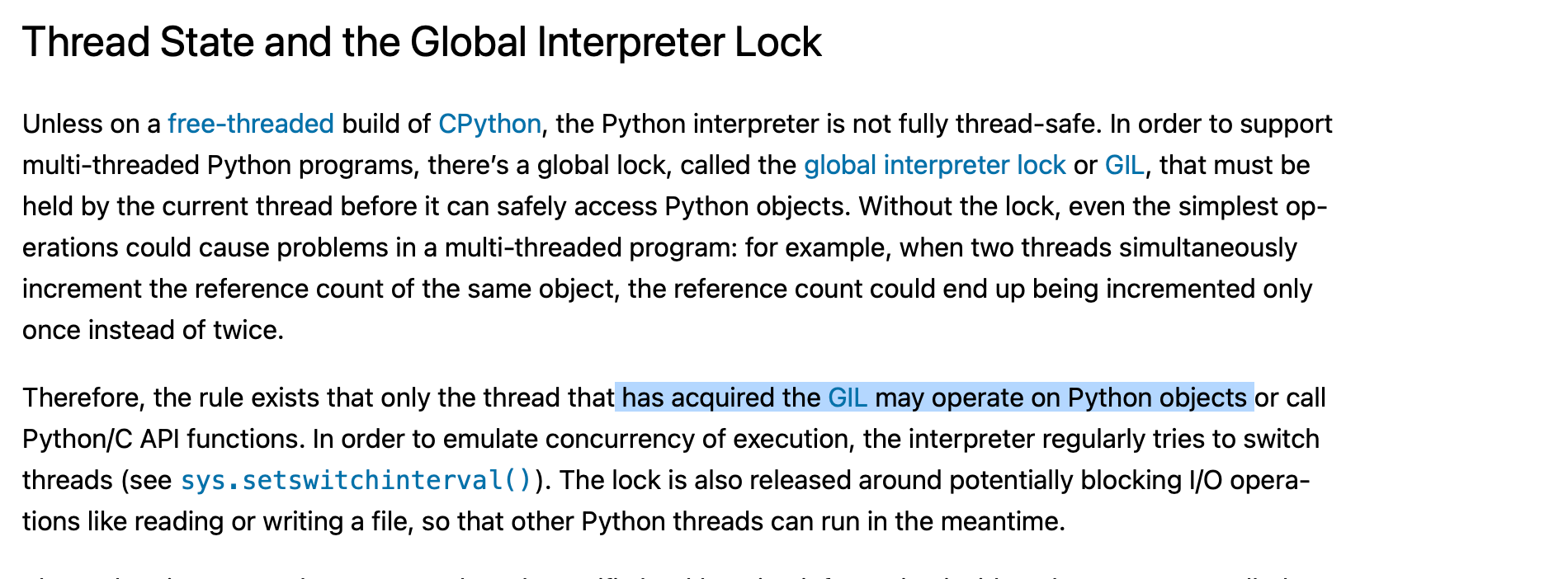

In the normal GIL-enabled CPython build, garbage collection runs while holding the GIL. Since any other Python thread must acquire the GIL before touching Python objects, all such threads naturally block on the GIL mutex/condvar until GC finishes. Thus, GC is by nature stop-the-world and the interpreter does not need additional thread-suspension mechanisms (like when the GIL is disabled). Releasing the GIL during GC would allow other threads to mutate object graphs and corrupt the GC state, so CPython never releases the GIL during scavenging (Starting from CPython 3.14, there is an incremental GC).

When Python is built in free-threaded mode (gil disabled), many threads may manipulate object concurrently (the ref counts would not be stable). In this case, the collector must stop the world (suspend all threads and wake them once it is safe), otherwise reference counts would not be stable and everything would collapse.

To reduce contention in the free-threaded build, CPython introduced

Deferred Reference Counting. Objects that support deferred counting do not

update their reference count on each stack mutation. This avoids the prohibitive cost of atomic increments on hot paths. Instead, deferred counts are merged during garbage collection by the collector; failing to merge them correctly before scavenging would naturally lead to use-after-free defects.

CPython now supports sharing data structures, such as lists and dicts, across threads without heavy locking (which could introduce a prohibitive tax). In these cases objects cannot be freed immediately (e.g. during a list resize) until all readers have stopped touching them (delayed freeing). CPython uses a QSBR (Quiescent-State-Based Reclamation) mechanism to delay frees until it is safe, basically a memory region is reclaimed only when all threads have passed through a quiescent state that guarantees they hold no references to that region without proper synchronization (objects are queued in a delayed queue with a QSBR goal).

In CPython, weak references allow an object to be referenced without preventing its garbage collection. When an object is about to be destroyed, CPython automatically clears any associated weak references and triggers their callbacks (all weakrefs for an object are internally hosted inside a linked list). This ensures that weak references never become dangling pointers and prevents any possibility of memory corruption or use after free within Python code.

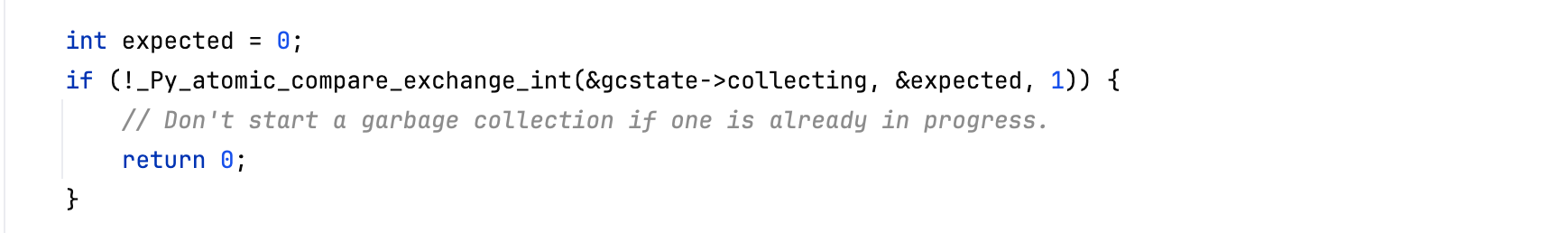

Another concern is the possibility of concurrent or re-entrant garbage collection. CPython’s cyclic gc stops the world while scanning object graphs (e.g when visiting mimalloc heaps), but it will temporarily wake up threads before invoking finalizers or weakref callbacks. If another thread triggers a new full gc cycle during this window, the interpreter could observe inconsistent gc state (e.g CVE-2021-44964). To prevent such situations, CPython uses a lock-free mechanism, that is, an atomic state variable is hosted and an atomic compare-and-exchange or CAS primitive is utilized to ensure that only one thread can trigger a gc cycle at a time, without relying on heavy locking. Re-entrant or concurrent attempts to start a gc cycle are simply ignored until the current cycle completes.

When the gil is disabled, CPython uses mimalloc as the underlying memory allocator (default allocator when gil is enabled is pymalloc but one can also build with mimallloc). Memory allocators typically have guards against double frees, for instance, in cpython mimalloc, each time a block is freed, there is an integrity check that verifies if a block is already living in one of its free linked list (the check is linear and enabled if secure mode is on; yep no free lunch).

static mi_decl_noinline bool mi_check_is_double_freex(const mi_page_t* page, const mi_block_t* block) {

// The decoded value is in the same page (or NULL).

// Walk the free lists to verify positively if it is already freed

if (mi_list_contains(page, page->free, block) ||

mi_list_contains(page, page->local_free, block) ||

mi_list_contains(page, mi_page_thread_free(page), block))

{

_mi_error_message(EAGAIN, "double free detected of block %p with size %zu\n", block, mi_page_block_size(page));

return true;

}

return false;

}For more details, you can refer to the notes I shared.

Writing programs in memory-safe languages is often the best choice, even for experienced programmers, as low-level programming greatly increases cognitive load. However, using high-level languages does not eliminate all vulnerabilities; other classes of flaws remain possible (code injection, race condition, logical errors etc.).

Virtual machines and interpreters can still contain memory defects. While reference counting avoids use after free vulnerabilities, failing to manipulate correctly the reference count (reference miscounting or reference bugs) can still lead to temporal flaws. A recent example is the Wiz Redis vulnerability where potential Lua VM sandbox escape was caused by a use-after-free triggered while compiling Lua scripts arriving through the event-loop command buffer.

In this post we provided an idea of how CPython prevents several classes of defects, including temporal and spatial violations. The goal was to illustrate that properly implementing a safe runtime demands a lot of effort and why implementing safety guards outside virtual machines is necessary to reliably protect runtime workloads.

For more details, I have shared my draft notes: https://github.com/mouadk/CPython-Through-Cybersecurity-Glasses/tree/main, which will be updated soon to cover more topics and include fixes for typos, clarifications, and other improvements.